|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

photo by History Examiner |

photo by The Brookline Connection |

|

photo by Brookline Connection

|

photo by History Examiner |

photo by History Examiner |

|

photo by Andy Cunningham

|

photo by Post Archives |

photo by History Examiner |

|

photo by Heinz History Center Library and Archives

|

photo by Underwood Archives

|

Pittsburgh Bureau of Fire (PBF), provides fire protection, emergency medical services and hazardous material mitigation to the city of the City of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. In all the department is responsible for 55.5 square miles of response area with a population of over 300,000 people.

Help Needed If you are a firefighter in the City of Pittsburgh, we need your help to verify the station information shown below is current and correct.

If you have any information to add to this section, please email us |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

photo by Collection of Wesley Pickard

|

photo by the Post-Gazette

|

|

|

|

|

| History of fire protection in the City of Pittsburgh

|

|

The department started out as a volunteer fire department and officially transitioned to a fully paid department on May 23, 1870. Over 30 years later in 1903 a group of Pittsburgh Firefighters sought to improve working and living conditions of those serving in the department. They formed an association known as the City Fireman’s Protective Association. By September 1903, the very first International Association of Fire Fighters union was organized, IAFF Local #1.

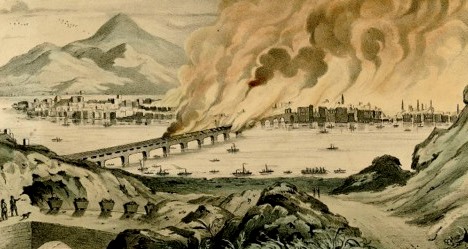

Great Fire of Pittsburgh

The Great Fire of Pittsburgh occurred on April 10, 1845, destroying a third of the city and causing between $6 million and $12 million in damage. While having little effect on the culture of the city except to spur further growth, it would provide a temporal reference point for the remainder of the century and beyond.

The dawn of April 10, 1845, brought a warm, windy day. During a brief interlude in the winds just before noon, Ann Brooks, who worked on Ferry Street for Colonel William Diehl, left unattended a newly stoked fire lit to heat wash water. A spark from this fire ignited a nearby ice shed or barn. The fire companies responded, but got nothing but "a weak, sickly stream of muddy water" from their hoses, and the flames quickly spread to several buildings owned by Colonel Diehl, including his home, and to the Globe Cotton Factory. The bells of the Third Presbyterian Church had given the original alarm, but the church itself was only preserved by dropping its burning wooden cornice into the street. Once saved, its stone walls served as a barrier to the further spread of the fire toward the north and west. Then the wind veered to the southeast and gave the fire added vigor; a witness stated that "the roar of the flames was terrific, and their horrible glare, as they leaped through the dense black clouds of smoke, sweeping earth and sky, was appalling."

By 2:00 pm, with the fire throwing embers into the air that then started new fires where they landed, many of the citizens who had been fighting the flames instead fled to save their own possessions. During its height, between 2:00 and 4:00, the fire marched block by block through the intermixed structures of Pittsburgh's poor and elite, residences and businesses, with "the loftiest buildings melting before the ocean of flame," which consumed wood, melted metal and glass, and collapsed stone and brick. The Bank of Pittsburgh, thought to be fireproof, fell victim when the heat of the fire shattered the windows and melted the zinc roof, the molten metal igniting the wooden interior and burning all except the contents of the vault. A similar fate met the grand Monongahela House, called the "finest Hotel in the west," when its cupola caught fire and collapsed within, resulting in a total loss. The mayor’s offices and churches fell. As it spread up Second Street to Market Street it destroyed the region where the city’s physicians had been concentrated

Although the flames were intense, they moved slowly enough that residents had time to remove themselves and many of their belongings. Some fled to the highlands to the east (the modern Hill District), then undeveloped except for the newly built courthouse, an area which remained untouched by the flames. Of those who fled south to the Monongahela River, some were able to cross the Monongahela Bridge (located at the site of the present Smithfield Street Bridge), which connected the city to the southern bank of the river and was the first of what would be many bridges spanning Pittsburgh’s rivers. However, this soon became congested, and then the wood-covered structure ignited, being fully consumed in about 15 minutes and leaving nothing but its supporting pylons. Those counting on riverboats to take their belongings away fared less well because the boats that did not flee burned, leaving the refugees to pile their belongings on the riverbank. Most of this material was burned by the advancing flames, stolen or looted, while the escaping population was typically left with nothing more than they could carry. The docks and warehouses on the waterfront were likewise consumed, and as with the residents, attempts to save materials from the warehouses by bringing them to the riverbank only delayed their destruction. The fire followed the river into Pipetown, an area of workers' housing and factories, again spreading destruction. It only halted when the winds died down about 6:00, and by 7:00 it had fully abated within the city, having burned its way to the river and cooler hills. The factories of Pipetown burned on until about 9:00. Throughout the night, there were occasional flare-ups along with the repeated sounds of buildings collapsing

The burgeoning fire companies of the city found themselves overwhelmed. In a city flanked by rivers, their equipment and infrastructure were insufficient to bring water to the site of the blaze. The volunteer companies, which functioned more as gentlemen's clubs than professional firefighting organizations, lost most of their hoses and two of their engines in the blaze.

Help also came from individual volunteers. While the vessels on the Monongahela fled the city, those on the Allegheny side, to the north, were active in ferrying refugees across the river and bringing back men from Allegheny City to help fight the flames and evacuate residents. Among those crossing to help was a young Stephen Foster, who would later become known as the 'father of American music'.

Congregation members rushed to save the Third Presbyterian Church. The thirteen-year-old John R. Banks went to the roof of the Western University of Pennsylvania (forerunner of the University of Pittsburgh) in an attempt to prevent it from being ignited by the falling cinders. However, as described by a witness, "the cupola of the University burnt for a few minutes like paper and went down." The home of the University president was also lost. Others went into the evacuating areas to loot the abandoned homes and goods left in the streets. One hotel was saved within the burned area by using gunpowder to blow up the adjacent structures, creating a gap that the flames did not cross

By the morning of April 11, a third of the city was burned to the ground, leaving only scattered chimneys and walls amid the ruins, although occasional buildings were inexplicably left untouched amid the destruction. It was said that "the best half of the city" had been burned, an area representing 60 acres, and the entire Second Ward of the city had just two or three dwellings untouched. Local artist William Coventry Wall captured this landscape in a series of paintings which he quickly had printed as a lithograph. This was published in Philadelphia and saw a broad market, as did prints by Nathaniel Currier in Boston and James Baillie in New York (both of whom based their works on newspaper reports), in line with a growing market for "disaster prints." The fire destroyed as many as 1200 buildings, while displacing 2000 families, or about 12,000 individuals, from their homes. Household belongings were piled on the hills surrounding the city. Surprisingly, only two people died. One was lawyer Samuel Kingston, who was thought to have returned to his house to rescue a piano but apparently lost his bearings in the heat and smoke, since his body was found in the basement of a neighbor's destroyed house. The other body was not found until weeks later, and is thought to be that of a Mrs. Maglone, whose family had advertised not having seen her since the fire. Estimates of the cost range from $5 to $25 million, with one recent author placing it at $12,000,000, which he equated to $267 million in 2006 dollars. Almost none of this was recoverable, as all but one of Pittsburgh's insurers were bankrupted by the disaster.

Local ministers declared the disaster to be the judgment of God upon the iniquities of the industrial city and the mayor of neighboring Allegheny City called for fasting, humiliation and prayer. The mayor and attorney Wilson McCandless personally traveled to the state capitol of Harrisburg to appeal for relief, and their petition was supported by Governor Francis R. Shunk. The Legislature agreed to grant the city $50,000, to refund taxes for destroyed structures, and to give the entire city a three-year break from taxes. The latter had an unanticipated disadvantage, forcing public schools to remain closed for want of funding, while the Legislature subsequently made attempts to renege on some of the relief money they had granted. Public and private donations totaling almost $200,000 were received from as far away as Louisiana and even Europe, while several cities and towns in the United States, such as Wheeling and Meadville, Pennsylvania, made donations of commodities such as flour, bacon, potatoes and sauerkraut. The moneys were distributed on a sliding scale to those making claims, the last being disbursed the following July.

The first response of the city was one of despair, as can be seen in reports to newspapers in other cities and in initial descriptions:

It is impossible for any one, although a spectator of the dreaded scene of destruction which presented to the eyes of our citizens on the memorable tenth of April, to give more than a faint idea of the terrible overwhelming calamity which then befell our city, destroying in a few hours the labor of many years, and blasting suddenly the cherished hopes of hundreds – we may say thousands – of our citizens, who, but that morning were contented in the possession of comfortable homes and busy workshops. The blow was so sudden and unexpected as to unnerve the most self possessed.

However, this mood did not last long and the city was shortly rebuilding. The sudden dearth of structures resulted in skyrocketing property values and a coordinate construction boom that quickly replaced many of the destroyed structures, and after two months, even though "passways were scarcely opened through the heaps of stone, brick and iron," 400–500 new buildings had been erected in the burned area. Although the new homes, warehouses and shops were built of better materials and improved architecture compared to those destroyed, the problems remained, with industrialist Andrew Carnegie commenting in 1848 on the fire-prone wooden buildings, and later on the smoke and soot-filled air. The market for replacement homes and household articles further invigorated the industries, and the fire was held to have "spurred the city to greater growth," an attitude encouraged by Pittsburgh's industrialists. This role of the fire was commemorated a century later with a celebration of the anniversary.

The Great Floods of 1907 & 1936

With three rivers flowing through the area, flooding has naturally been a concern for Pittsburgh. While the fire of 1845 was due in part to a dry spring, another devastating disaster came from an over abundance of rain and snow melt.

On March 14, 1907, heavy rain began to fall and that combined with a quick snow melt sent the rivers in Pittsburgh over their banks. Bridges collapsed, towboats capsized, and towns all up and down the Allegheny, Ohio, and Monongahela Rivers were submerged. Flooding began at 20 feet and the deluged topped out at 35 feet. This was 13 feet over the danger line and marked the highest the rivers had crested in 75 years.

Ironically, nearly to the day 29 years later on March 17, 1936, the Pittsburgh area once again found itself underwater in what has become known as the Great St. Patrick’s Day Flood. Once again heavy rains and rapidly melting snow sent the rivers rising. The flood claimed 62 lives, with 500 injured and 135,000 people left homeless. The city suffered millions of dollars in damages to homes, businesses, and industries.

Today, the U.S. Army Corps of engineers manages the region’s flood control efforts, comprised in part by 16 reservoirs controlling 40% of the drainage basin in the upper Ohio valley.

The Equitable Gas Explosion

Another disaster that wreaked havoc on Pittsburgh was one that could have been avoided. On November 14, 1927, 28 people were killed and between 500 and 600 were injured when an enormous gasometer, or gas storage tank, exploded in what was often referred to as the Equitable Gas Explosion.

Located on the North Side, on Reedsdale Street, near the present site of the Rivers Casino, the gas tank at the time was the largest in the world and when filled, contained 5,000,000 cubic feet of natural gas. Weeks before the explosion, the tank had been emptied, but when a leak was reported in the tank repairmen went to repair it with blow torches. Remaining vapors in the tank exploded. The enormous circular tank shot into the air and then exploded over the North Side. Eyewitnesses said the tank “shot into the air like a balloon. A ball of fire traveled higher than the tip of Mt. Washington, across the Ohio River from the scene. Sections of the steel framework went up hundreds of feet to crash through roofs and into the streets.”

Debris from the tank rained over the North Side. The force of the blast knocked down homes, telephone, and power lines. Residents were blasted out of their beds and police officer rescued a small child who had landed in the Ohio River. Water lines were severed, flooding the devastated region. Windows downtown were shattered and frantic survivors lined up at the morgue to search for relatives. The tanks were never rebuilt as that area of the North Side tried to recover.

Although each of the above tragedies devastated the area and changed the city, nevertheless, Pittsburghers each time rose to overcome these calamities.

The Gamewell Alarm System

Aside from the rigors of firefighting, the crews that manned the station in the early years had quite a lot to do while awaiting the next call to duty. At the dawn of the 20th century, the Pittsburgh Bureau of Fire utilized an alarm network called the Gamewell System.

Gamewell was first installed in the 1860s and the system expanded as the city grew. The network connected red fire alarm boxes around the city with the Pittsburgh headquarters. The alerts were also sent to all of the city's neighborhood stations.

Prior to 1916, there was only one shift of firefighters working the station. On July 10 of that year, an entire second shift was hired.

This dropped the work week from almost continuous duty to just eighty-four hours a week.

There was a duty officer assigned to watch at all times. Their job was to sit at the watch desk on the apparatus floor and listen to the Gamewell System's gong alarms. Additional high-priority telephone alarms were transmitted over the city house line from headquarters.

The person on watch also had to greet anyone coming into the station. At night he had to manually hit the big gong if a telephone alarm came in from headquarters, and turn on the lights. Standard gong alarms were also entered into the log book, no matter which company the alert was for.

There were prearranged responses for six alarms, with companies moving up to fill in vacant stations on each alarm. It was an important job to be on watch, and if you dozed off or wandered away your company could miss a fire.

The Gamewell alarm system was eventually replaced with a network of mechanical call boxes located on telephone poles along city streets. These red boxes remained in place until the 1980s when they were replaced with the "911" emergency telephone system.

The Fire Hydrants

The fire hydrants that dot almost every sidewalk in Pittsburgh are not a uniform lot. They come in different designs and sizes. Some are tall and thin while other are fat and short. Some have pointed caps and some have disks on top. While many hydrants in the city are painted in traditional red-and-white, many more have been altered aftermarket in imaginative color schemes. And some, of course, have been tagged.

The hydrants tell a brief history of public works in a given neighborhood. A date is stamped onto every hydrant telling when it was installed, and a name indicates the manufacturer, such as American Darling of Beaumont, TX, or Kennedy of Elmira, NY. The manufacturers also stamp other important information onto their hydrants, a prime example being these two from the 1980s. They bear the slogan: City of Champions.

Sources:

Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Popular Pittsburgh

The Brookline Connection

The Ongoing History of Pittsburgh

Adams, Marcellin C. (1942). "Pittsburgh's Great Fire of 1845". Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine

Arensberg, Charles F. C. (1945). "The Pittsburgh Fire of April 10, 1845". Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine

Cook, Donald E., Jr. (1968). "The Great Fire of Pittsburgh in 1845, or How a Great American City Turned Disaster into Victory". Western Pennsylvania History

Dawson, Charles T., ed. (1889). Our Fireman. The History of the Pittsburgh Fire Department from the Village Period until the Present Time. Pittsburgh.

Foster, J. Heron (1845). A Full Account of The Great Fire at Pittsburgh of the Tenth Day of April, 1845. Pittsburgh: J. W. Cook.

Hoffer, Peter Charles (2006). Seven fires: the urban infernos that reshaped America. New York: PublicAffairs Books.

|

|

|

|

|

|